Just over half of China’s 31 provinces and municipalities have announced increases in the minimum wage this year, and four major cities now have a monthly minimum wage of 2,000 yuan or above, the highest being Shanghai at 2,300 yuan per month, state-run media announced last week.

While the 17 increases so far this year are certainly an improvement on the nine last year, the rate of increase across China has steadily fallen since the peak of 2011, when 24 regions increased their minimum wage rates by an average of 22 percent.

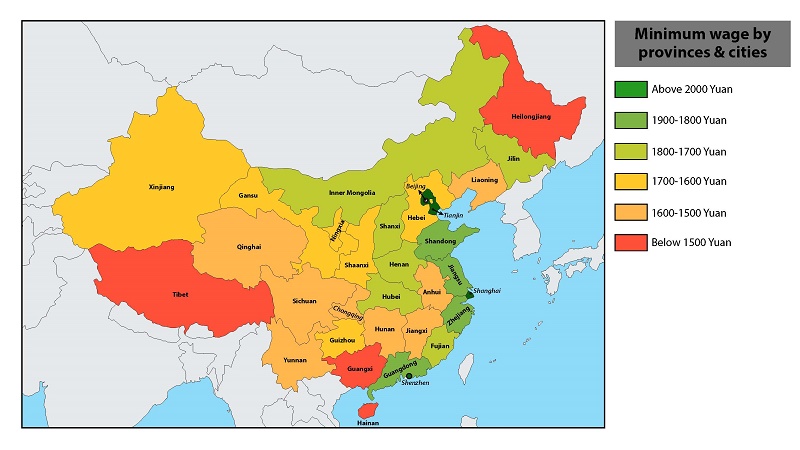

Minimum wage levels in China in 2017: Based on the highest rate in each region

Moreover, many regions are reluctant to make any increase at all. The economic powerhouse of Guangdong, for example, announced in March this year that it would henceforth only increase its minimum wage every three years rather than the standard two years. The current minimum wage levels in Guangdong, which have been in place since May 2015, range from 1,895 yuan in Guangzhou to 1,210 yuan in fourth tier cities. Shenzhen sets its minimum wage independently of Guangdong and it currently stands at 2,130 yuan per month.

The neighbouring and largely impoverished province of Guangxi has not increased its minimum wage since January 2015 and it remains the lowest in China, ranging from 1,400 yuan per month in the capital Nanning to just 1,000 yuan in its smaller cities. The minimum wage in the sprawling metropolis of Chongqing meanwhile has remained at 1,500 yuan per month since January 2016.

Even in cities with a minimum wage in excess of 2,000 yuan per month, income gets rapidly eaten up by rent, which can account for more than half of residents’ wages, according to a survey by the Shanghai-based E-House China R&D Institute. In the national capital Beijing, the average rent is 2,748 yuan a month, equal to 58 percent of average income. Rent accounts for 54 percent of income in Shenzhen and 48 percent in Shanghai. In 34 of the 50 cities surveyed, including Guangzhou, Tianjin and Hangzhou, rent accounted for between 25 and 45 percent of income.

Higher rents in major cities have forced people to move further and further away from the centre, thereby increasing the amount of time and money they have to spend on transport. And as greater numbers of people move to the outer suburbs, this in turn has led to residential rents in those districts increasing.

Last week’s China News and People’s Daily reports on the minimum wage were likely designed to frame the official media agenda prior the 19th Communist Party Congress and show that the government is taking concrete steps to improve the lives of ordinary workers. However, the minimum wage has never been a living wage in China, and even with the most recent increases, it still falls well short of being a decent wage for ordinary families. In most cities, the minimum wage is usually only between 20 and 35 percent of the average wage, barely enough to cover accommodation, transport and food costs.

The Chinese government routinely highlights the need to boost domestic consumption but the real purchasing power of ordinary workers in factories, construction sites and in service industries remains at a very low level.